Three years ago I applied for a job at spotify where I presented an impassioned (and somewhat halfbaked) thesis on how the platform was missing out on the greenfield opportunity to become more social. Whereas soundcloud was a place where djs and indie kids hung out, I always found myself in an echo chamber of my own algorithmically-derived tastes on spotify.

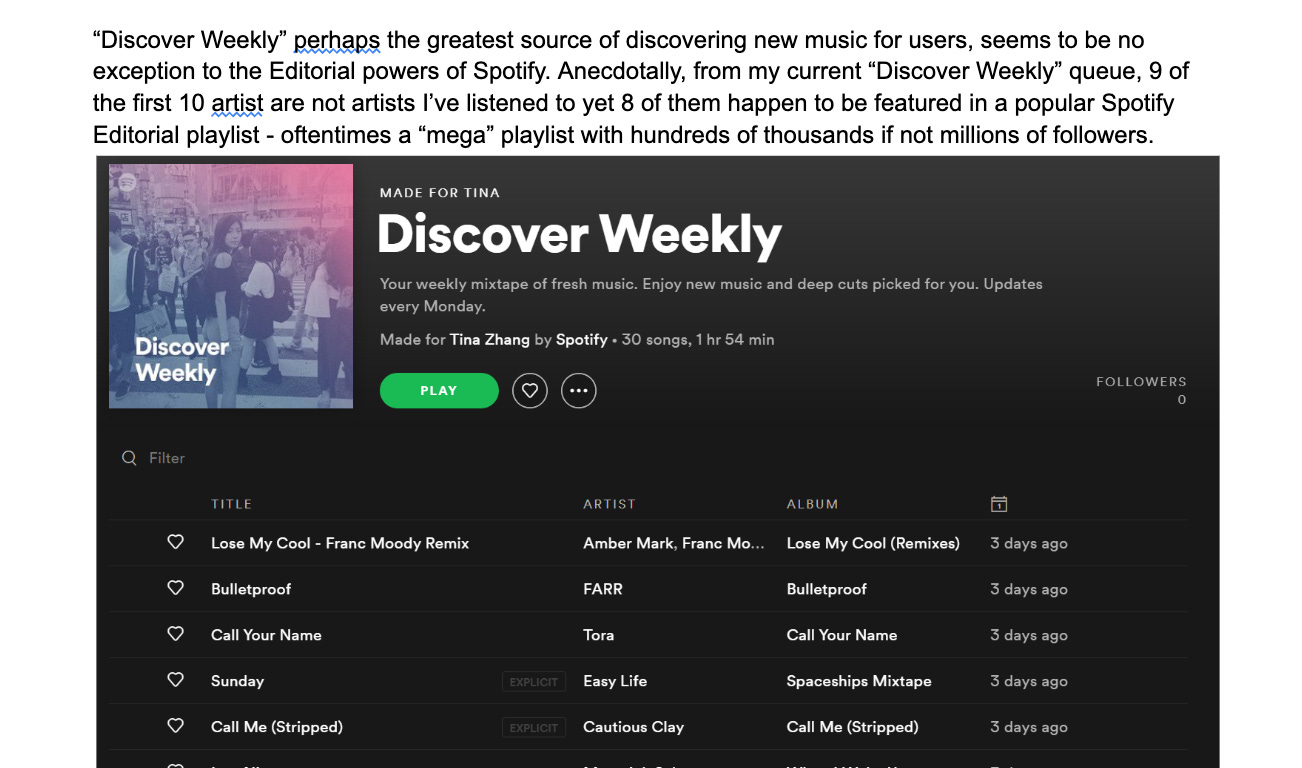

Among the more controversial takes I had was that the platform was pushing specific songs to its users via its personalized and editorial playlists. I noted that from my current discover weekly queue, 9 of the first 10 artists are not artists I’ve heard of and yet 8 of them happen to be featured in a popular spotify editorial playlist.

Spotify, I argued, had a heavy hand in influencing what users listen to via these ‘personalized’ playlists, and thus which songs go on to become hits. And the more Spotify is able to influence what its listeners consume, the greater power it has to negotiate with record labels (its main cost driver).

In case it’s not clear, I never heard back from the job.

Last week I read kyle chaykla’s essay in The New Yorker on finally quitting spotify. Chaykla has his own reasons, but notes a noticeable shift towards algorithmic recommendations “where listeners are being conditioned to rely on what spotify feeds them rather than on what they seek out for themselves”. For instance, the ux in the latest update makes listening to complete albums or discographies harder but pushes users to consume singular songs / hits.

This is by design, chaykla observes — or in an age-old tech adage, a feature not a bug. It’s part of the broader theory of platform decay or more colloquially known as “enshittification”: over time, companies seek profitability and shareholder value at the expense of their users, creating products with less and less bang for their buck.

The decay of a consumer platform doesn’t particularly bother me however (more room for disruptors). Similarly, as an avid consumer of short-form content, I understand the implicit agreement that when I open tiktok I am at the mercy of the algorithm (even if I did build it brick by brick). But the thing that scares me the most is this particular brand of stockholm-syndrome — where subconsciously, we become conditioned to want to be told what to like rather than putting in the work to decide for ourselves.

✦✧✦

The first album I ever purchased was kelly clarkson’s acclaimed second studio album, Breakaway (2004). I was in elementary school, and walked into the music section at my local used bookstore and diligently shuffled through every cd on display. I purchased clarkson’s cd because breakaway was my favorite song at the time, american idol was the best show on television and something about the messy, indie album cover felt inexplicably pretty to me. Music was a private experience (best done in your bedroom or walking around your cul-de-sac) and the songs that I fell in love with were things that I truly loved.

In middle school, I had an english teacher ask every student to present their favorite song to the class. At the time, my music taste consisted entirely of what I found on youtube or random pockets of the internet (see below)

I can’t remember what song I chose, but I do remember subtly taking notes on what everyone else had picked so I could go home and listen to their songs. I was suddenly aware that the songs I listened to weren’t just things I consumed in private, but signaled something about me. I didn’t fully grasp what it meant to have good taste, but I did know that I did not want my classmates to think the songs that I picked were weird.

✦✧✦

There’s a lot of discourse right now on personal style and taste — who gets to have it, how to find it. Not everyone agrees on if taste can be taught, but the unspoken agreement is that nobody, and certainly not you or I, wants to have bad taste.

This fear drives a lot of why we seek arbiters of taste in the first place. We can avoid risking appearing un-stylish if we look to our preferred fashion authority (influencer, writer, editor) to tell us what is chic. But what’s odd to me is that no matter who you ask, everyone seems to love the row, toteme and khaite.

When I read pieces on “developing your personal style” established fashion people will often bemoan the increasingly homogenous view of style and then redirect us towards those who have made a name for themselves in branding their distinctive tastes. The issue is that not all of us can become chloe sevignys or maryam nassir zadehs no matter how hard we try — when I go through my camera roll sometimes I’ll look at an outfit that I wore a year or even a few months ago and be absolutely horrified that I ever left the house that day. And then suddenly, buying the ophelia sweater or a pair of nevada boots starts to seem like the perfect antidote to having bad taste.

✧✦

In doing research for this piece, I started to fall into a rabbit hole of essays on personal style. While in the throes of blog posts, newsletters and substacks, it dawned on me that I was wading through a canon of other peoples opinions. In the same way I want to be told what is chic, I also want to get to the “right” answer on what it means to develop taste.

This extends beyond relatively benign spheres like “personal style” or “music tastes” into the way we perceive the world, the way we speak, and how we form our identities.

Right now it feels like we’re reaching a point in time which I could only describe as a simmering malaise. It’s not a vibe-shift per se, but I can’t help but feel a sense of alienation from the sheer pervasiveness of internet culture (and this is coming from someone who had “chronically online” as a tiktok bio for 2 years). All of a sudden it feels like we’re all saying the same words in the same way at the same time.

The other day, on the phone with Ian, I accidentally described something as “demure” in passing. I immediately cringed, aghast that I now had to edit my personal lexicon just to not self-identify as chronically online.

And it’s not just our peers, but our coworkers, the brands we shop at, the public figures we admire are all collectively leaning into internet culture to the point of oversaturation. In the words of dan brooks, “we all speak phone”.

✦✧

Complaining that nobody has any original thoughts is ironically an incredibly unoriginal thought. But I often need the reminder to practice forming my own opinion especially if I want to be a more creative person.

Last summer I listened to an interview with emily bode where she made a passing comment that if we’re always looking to other people’s opinions, it becomes increasingly hard to create anything original. A few months later, I was sitting at a tech conference where a founder made an eerily similar comment. When asked for her advice to give to other founders, she responded simply, stop asking for advice.

Developing ‘good’ taste takes courage — but also trial and error. We have to put ourselves through a type of rejection therapy in being willing to be wrong (and have bad taste, and look stupid) in order for us to cultivate what we actually like. It takes having the space to reflect on what we like and don’t like, what felt organic, what embarrassed us, and why.

They say to become a better artist you have to surround yourselves with conversations that draw you closer to art. In order to better connect and appreciate and discern, we have to shift the way we consume, the way we reflect, and the way we make up our minds.

As a macro-optimist, I like to believe that taste can be developed, but it’s a practice that takes intention and consistency not just when you’re getting dressed, but in all facets of your life.

to develop personal taste we must first drop the idea that we’re looking for taste in the first place. when we were kids it was either you liked something or you didn’t. why is it now we must consider if other people like it, if it’s cool to like it etc.

is good taste good because it reflects personal authenticity or because it adheres to objective beauty/order? many people wondering!